My Father’s Custom

Listening to “Astronomy Domine” with my one-year-old daughter in her bedroom after her morning nap gave me a little bit of a revelation about where the highly modern construction known as Orthodox Judaism often goes wrong.

Religious conservatism in the modern and post-modern worlds is obviously a reaction against prevailing norms and morals. There was no “Orthodox” Judaism until there was Reform Judaism. Even the idea of “Judaism” was a defensive construction.

The most fervent religious people I’ve been around — regardless of denomination — have been living out a microcosm of this in their own lives. Their parents and communities weren’t that religious, they grew up feeling some lack, and they became hardcore to compensate.

Before I became a parent, I had that tendency myself sometimes. I took on religious stringencies in order to build some supportive structure for myself that I felt my parents and synagogues growing up failed to provide for me.

Now that I have a kid, though, it’s palpable that the holiest thing to do in any situation is to be present, use my instincts, and respond to my child in the way that will raise her to be a whole person. Sometimes religious observances are the tool for the job. Often they aren’t.

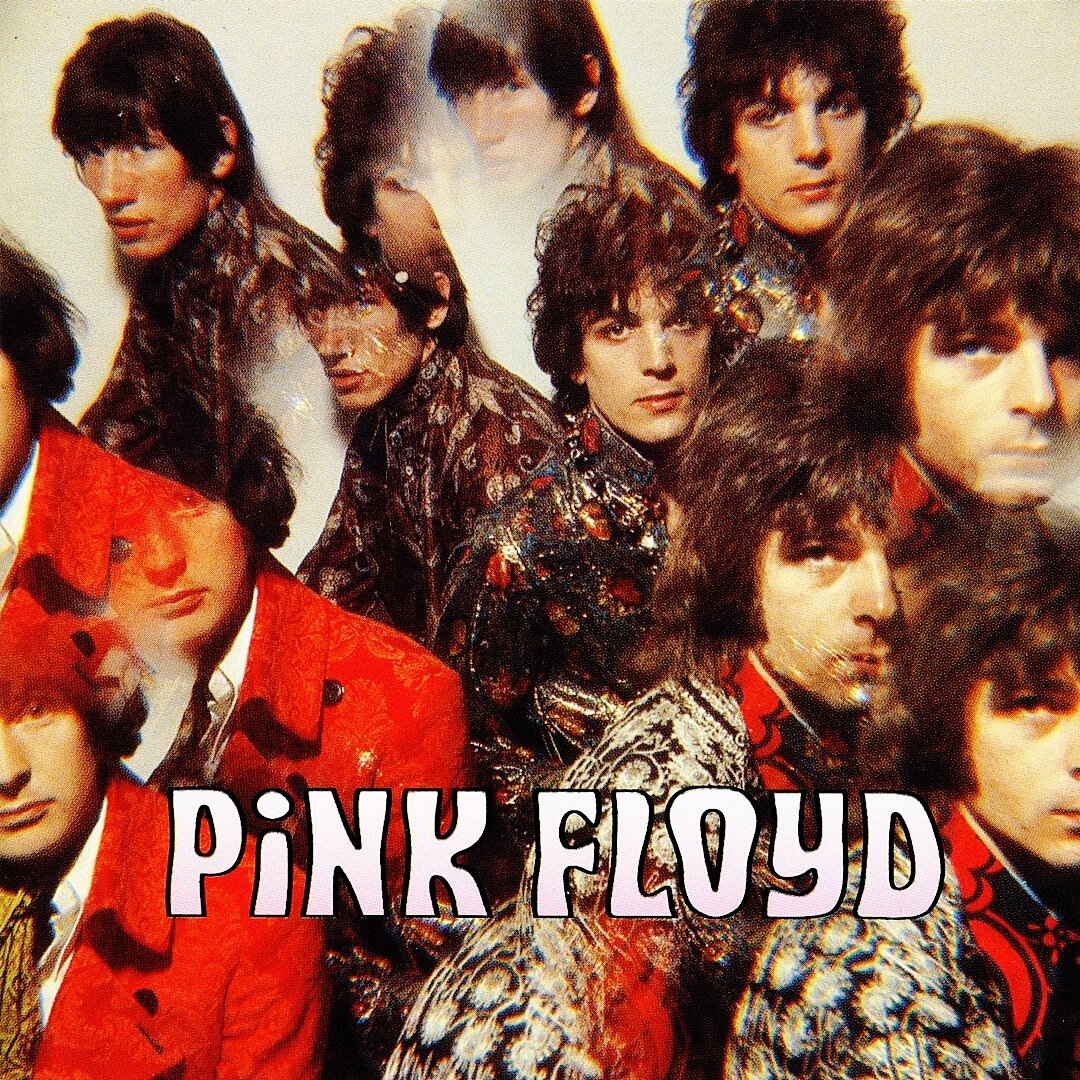

It’s much more reliable for me to reach into my memories of the things my parents did raising me that made me whole. Like listening to Pink Floyd with me in my bedroom. I remember lighting Shabbos candles, too, but father/daughter Pink Floyd feels 100% as Jewish to me.

That must be because there’s scarcely anything more Jewish — more religiously Jewish — than to uphold the customs (מנהגים) of your parents. You might say that Judaism is entirely a collection of things people learned from their parents and kept doing after they were gone.

My daughter’s grandfather — baruch HaShem, may he live to 120 — is still with us, but he clearly instilled his minhag firmly in me. On Sunday mornings, we listen to the British psychedelic rock of the 1960s and ’70s with our children.

My father did not lay tefillin on Sunday mornings. I do sometimes, but I’m not following my father’s minhag when I do so. If my child does, though, she will be, and she may want to do it more religiously than I did. This is where the aforementioned revelation comes in.

If I were to live my life by the extremely specific religious playbook known as the Shulchan Arukh (“The Set Table”), I would alienate myself from my parents. They have a hard enough time with my lightweight Conservative Movement kashrut and Shabbat observance as it is.

Every Jewish family knows this: clashes between different levels of observance tear apart families. Parents do the best they can with what they have. My parents did a stupendously good job raising me. If I were to flip out and become frum, it would dishonor them.

כַּבֵּד אֶת-אָבִיךָ וְאֶת-אִמֶּךָ לְמַעַן יַאֲרִכוּן יָמֶיךָ עַל הָאֲדָמָה אֲשֶׁר-יְהוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ נֹתֵן לָךְ

That’s the Fifth Commandment. It says, “Honor your father and your mother in order to lengthen your days on the earth HaShem your God gave you.”

You are not going to convince me, try as you might, that flipping out and going black-hat would not violate that commandment. For me. I’m talking about honoring my parents, no one else’s.

I honor my parents by doing the best things they did for me — like putting on Pink Floyd records — and by experimenting, which my dad did by buying Pink Floyd records in the first place. For me, adding in some daily spiritual practice is the latter sort of experiment.

If I do my job, my kid will inherit my synthesis as her father’s customs, and she will add to it her own experiments. The cycle continues. You can see in just this three-generation lineage how the pendulum swings both ways. The old ways wax and wane naturally.

Continuity is assured when customs are a grounding, comforting part of growing up. They become our own when we’re free to play with them. Otherwise, we either wear them like an ill-fitting costume, or we react against them, and they drop from our lineage.